“I can’t stop thinking about food.”

Ever felt that way?

It’s normal to think about food a fair bit, and occasionally overeat.

But what about when thoughts of food crowd out almost everything else? When you feel an anxiety that’s only relieved by eating?

Or when it seems like you don’t have any control over what, when, and how much you eat?

It might make you wonder…

“Do I have an addiction?”

Many of us throw the word “addiction” around lightly when we talk about our relationship with food.

But some people—including, perhaps, some of your clients—are truly suffering.

In this article, we’ll explore:

What food addiction is.How it’s different from overeating.Why certain foods have more “addictive” qualities than others.Who’s most vulnerable.

(Quick heads up: As a coach you can’t diagnose food addiction, but you can support and be an ally to your clients dealing with it. You’ll also want to refer out to a qualified practitioner. Learn more about that here).

Let’s get into it.

What is food addiction?

Food addiction means having emotionally-driven, persistent, and uncontrollable urges to eat—even when you’re not physically hungry.

It affects 2-11 percent of people in Western countries. (The rates are highest in the US, with some research showing as much as 11.4 percent of the population could be affected.)1

With rates so high, you likely know someone with food addiction. Or maybe you’re the one struggling.

How do you know?

Here are some signs of food addiction:

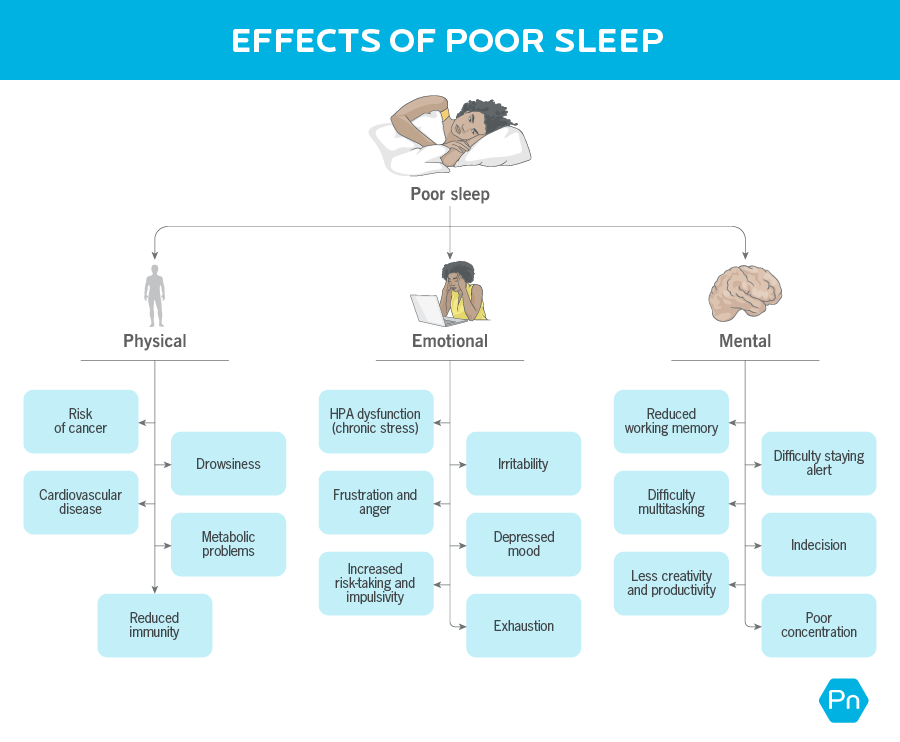

Craving increasingly large amounts of (usually) high-calorie processed foods in order to feel pleasure, energy, or excitement, or to relieve negative emotions, physical pain, or fatigue.Spending so much time thinking about and getting food, and recovering from overeating, that it crowds out recreational activities, professional obligations, and relationships.Continuing to overeat despite negative effects like digestive problems, unwanted weight gain, or mobility issues.Experiencing withdrawal-like effects—irritability, low mood, headaches or fatigue1,2—when you’re not eating.

How is food addiction different from other forms of overeating?

If you overeat at most of your meals, or have the occasional out-of-control binge eating episode, are you addicted to food?

Not necessarily.

Pretty much everyone experiences periods of overeating, and/or instances of binge eating.

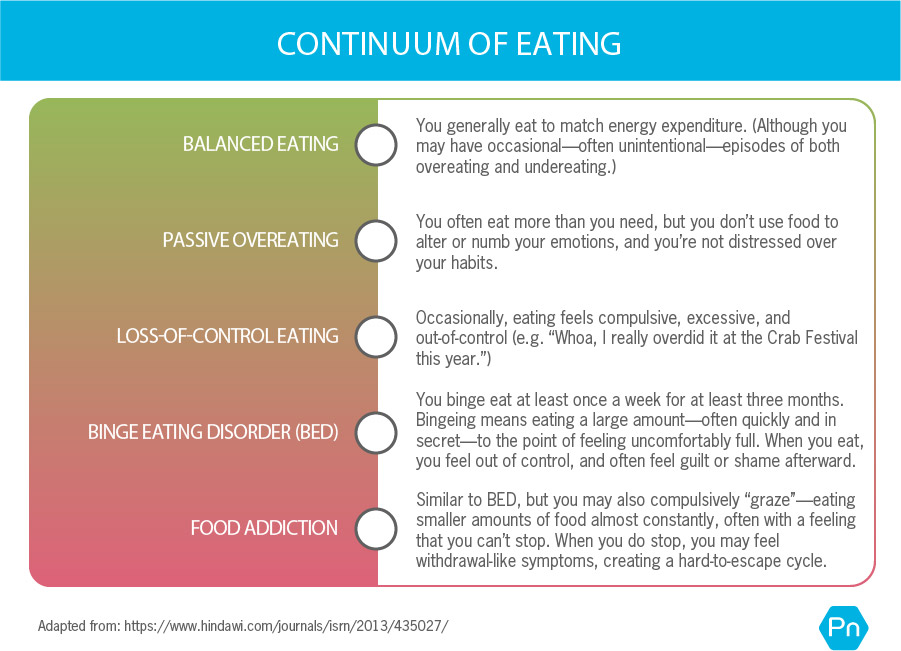

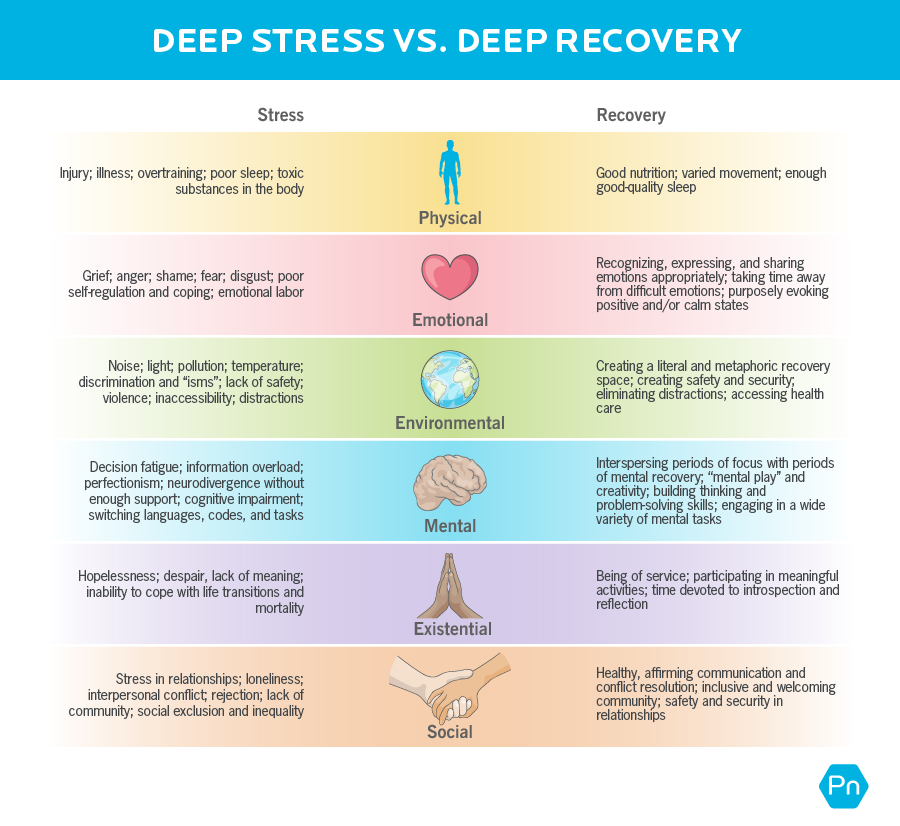

As the following continuum shows, it’s only when urges and compulsive behavior around food become severe, frequent, and chronic that a person can be diagnosed with an eating disorder or food addiction.3,4,5

As you may notice, binge eating disorder and food addiction share several major similarities.

But food addiction—which more closely resembles a substance use disorder—is more severe than BED because it causes even more life disruption.

How food addiction happens

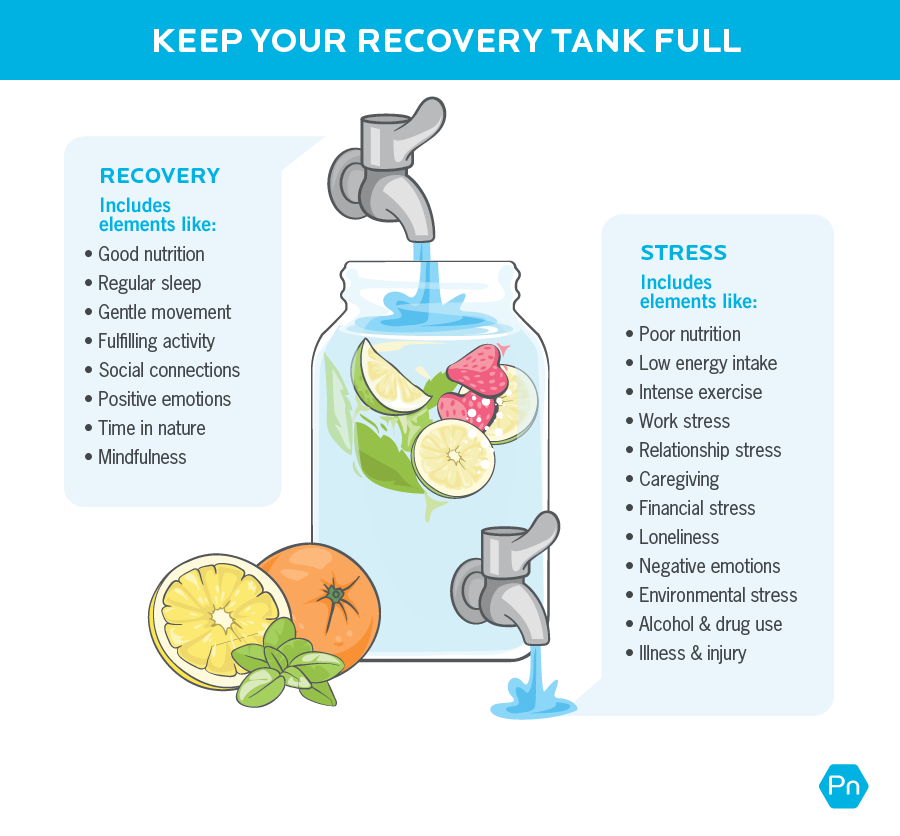

Food addiction isn’t caused by one single thing.

For example, you can’t just blame it on genetics.

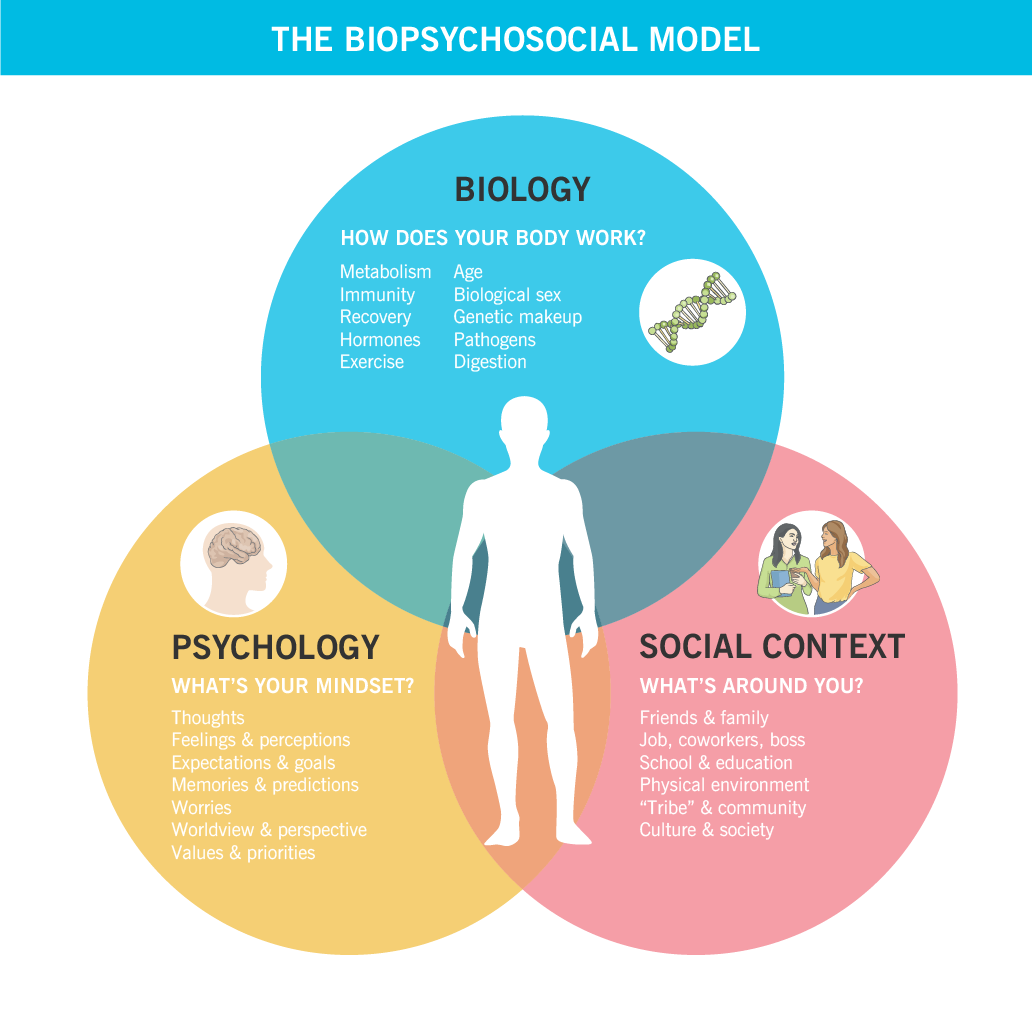

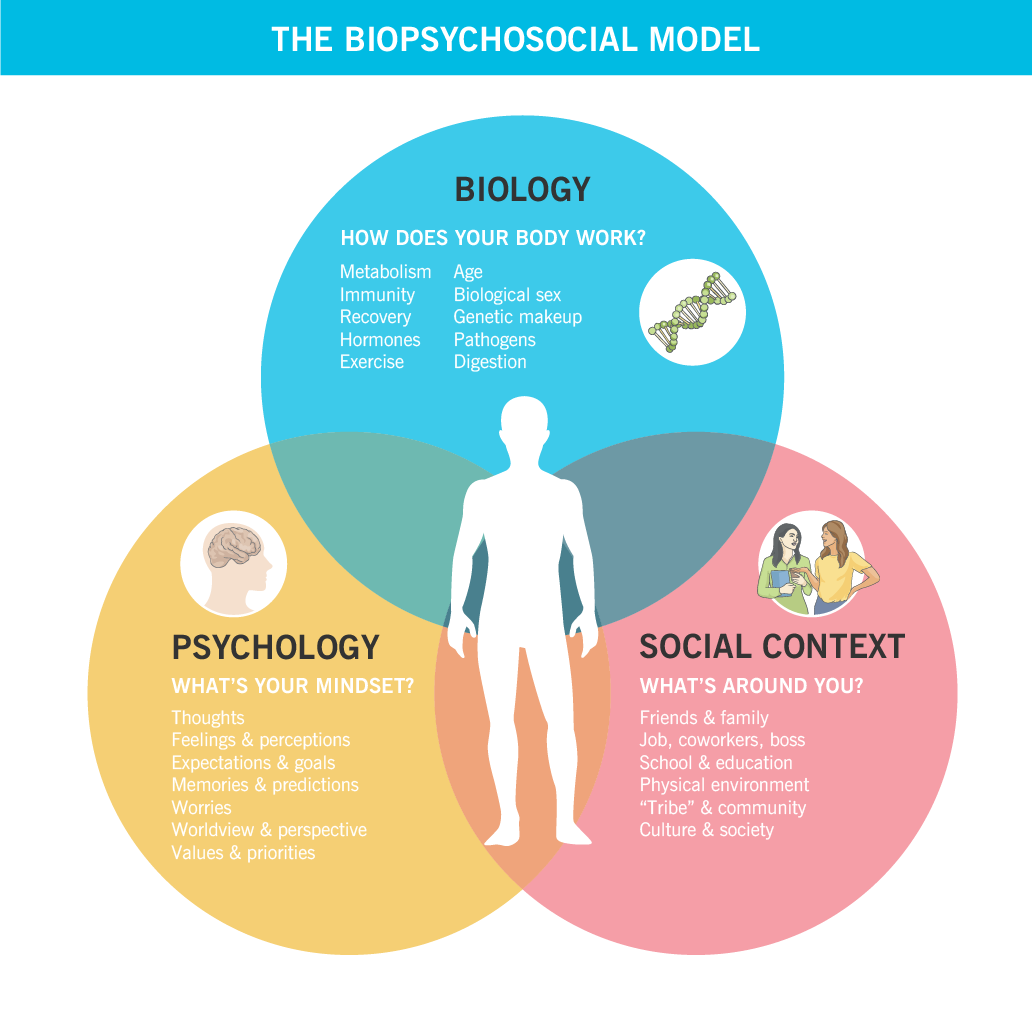

Factors like the amount of stress in someone’s life, how they respond to that stress, how lonely they feel, where they live, and who they spend time with also make an impact.

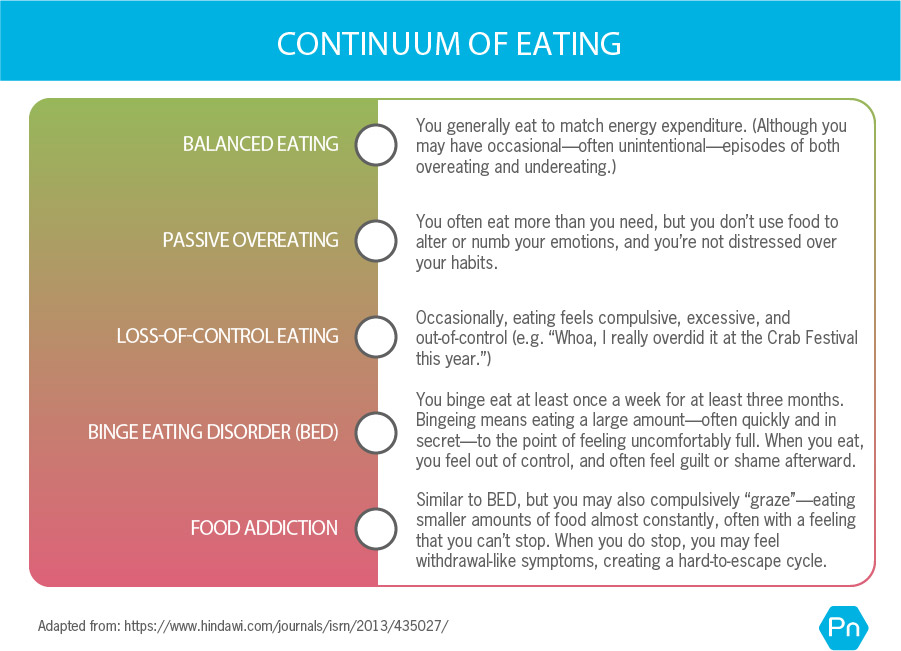

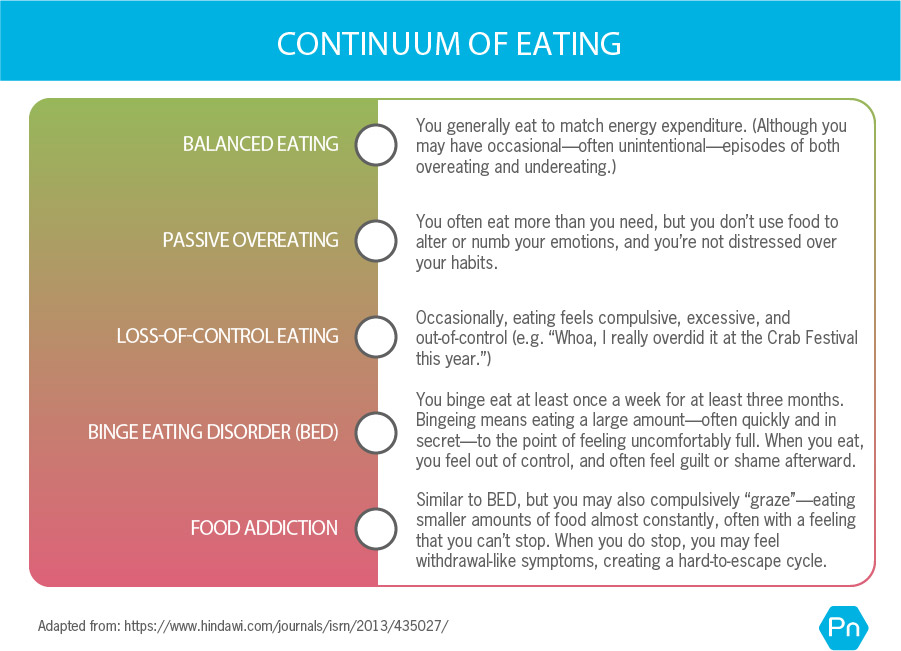

In other words, like most health issues, food addiction arises out of a jumble of biological, psychological, and social factors. (This multi-dimensional approach to understanding illness and health is called the biopsychosocial perspective.)

Let’s go into those categories now.

Biological factors: How does your body work?

In early human history, food scarcity happened on the regular.

To survive, humans evolved to overeat when food was abundant, especially when that food was tasty and calorie-rich.6,7,8 (Jackpot: avocado tree.)

But now, the instinct that once helped us survive makes it hard to stop eating.9

Highly-processed foods—especially those with a combination of sugar, fat, and salt—are the most difficult to resist.

Much like drugs and alcohol, these foods trigger a range of rewarding, feel-good neurochemicals, including dopamine. Highly-processed foods have this effect even when you’re not hungry.10,11,12

(In contrast, whole, unprocessed foods aren’t very rewarding when you’re not hungry, and it’s usually easier to moderate your intake of them.5,13)

These days, highly-processed foods are so accessible that you have to rely on your ability to self-regulate, or control your behavior, in order to resist them.

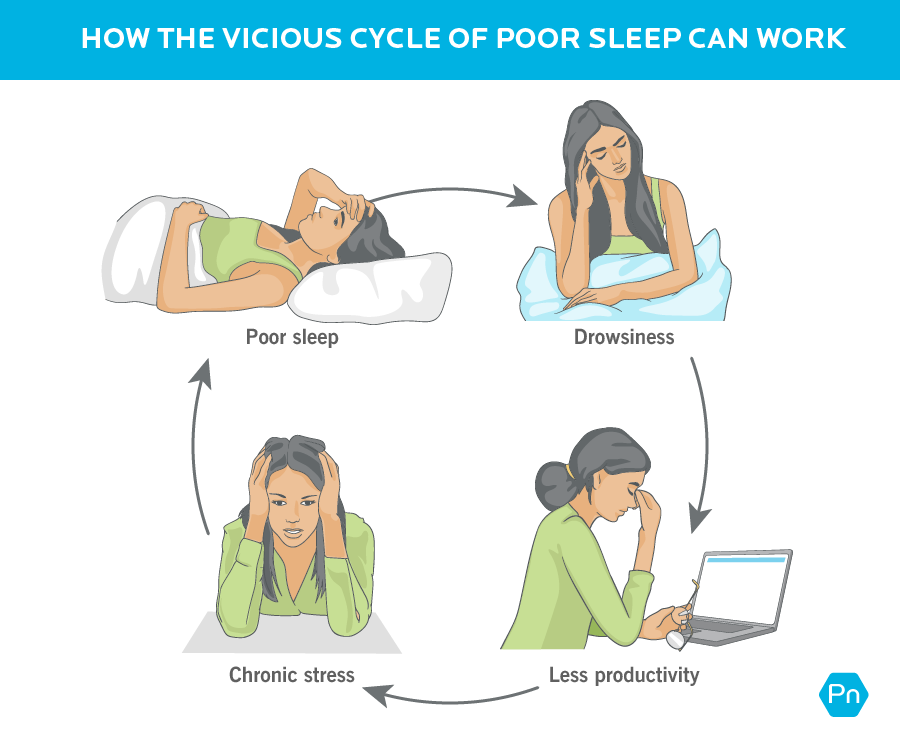

But people who deal with compulsive overeating (including those with food addiction) often have a hard time self-regulating.

Here’s why:

People with compulsive overeating may…

Struggle with impulse control, possibly because the planning, strategizing center of the brain (the prefrontal cortex) is impaired. This might be a hallmark of all addictions, and can contribute to poor recovery outcomes.14,15

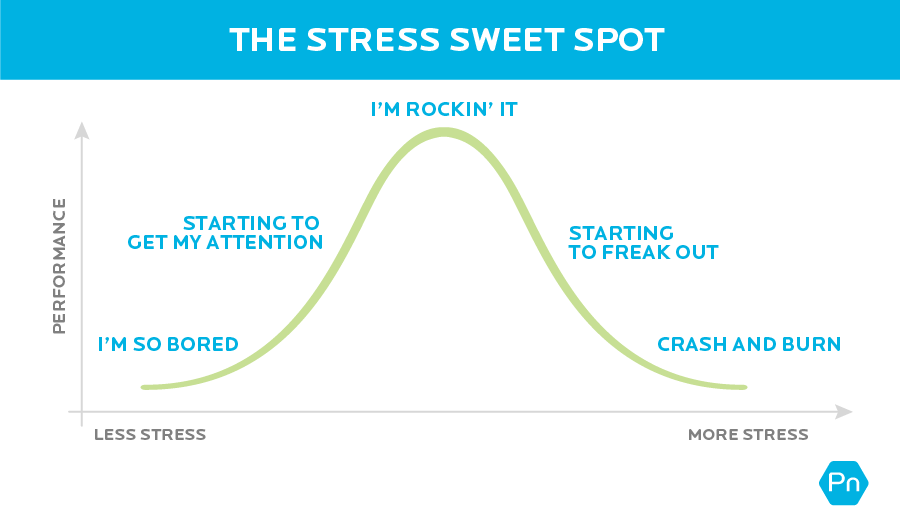

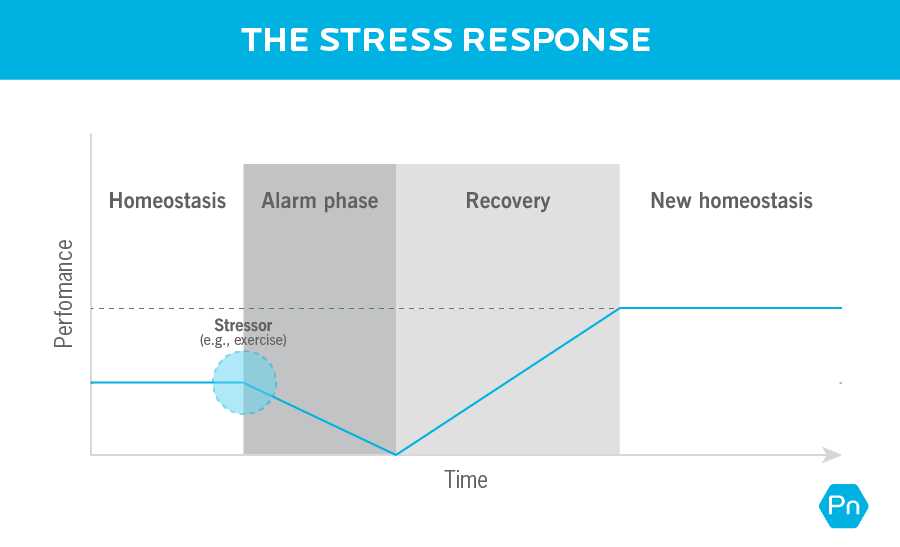

React more easily and intensely to stressors. They have a higher level of cortisol release than others.16 And because stress can trigger addictive behaviors, people who are more physically sensitive to stress may be more likely to use food (or drugs or alcohol) as a way to cope.

Get more pleasure from food (at first).17,18 They may have a bigger dopamine response to highly-processed foods, more motivation to seek out that response again, and stronger cravings.19

Get less pleasure from food over time. When you often overeat highly-processed foods, dopamine receptors become less responsive to those foods.20 This means that a bigger “hit” of food is required to achieve the same pleasurable effect.21,22,23

Dopamine: Why we like it, and how it hooks us.

Dopamine release happens in the nucleus accumbens, a brain region famous for its role in registering pleasure and reinforcing learning.5

Lots of things give you little dopamine boosts… eating a tasty meal when you’re hungry, connecting with friends and loved ones, and achieving goals. However, certain activities and substances—like drugs, gambling, and (yes) highly-processed foods—can produce unnaturally high surges of dopamine.

Here’s why that can become a problem:

The greater the dopamine response, the more pleasure you experience. The more pleasure you feel, the more motivated you are to repeat it.

When you experience a dopamine surge, you learn to associate pleasure with the specific activity or substance that caused it.

As that learning continues, your prefrontal cortex and your reward system get hijacked. You become focused on getting more of the thing. And you have trouble experiencing pleasure from anything else.

Over time, your brain adapts to these floods of dopamine.

This is called tolerance. Tolerance drives you to chase more of the pleasurable thing, yet you rarely feel satisfied.

This is the addiction cycle.

(Want to know more about what food characteristics people find irresistible—and even addictive? Read: Manufactured deliciousness: Why you can’t stop overeating.)

Psychological factors: What’s your mindset?

When we ask clients, most of them say they’re more likely to overeat when they’re feeling stressed, tired, or sad.

Research supports this observation: Stress, depressed mood, anger, boredom, and irritability are common triggers of binge eating16,24

Binge eating often further triggers feelings of guilt and shame, and these feelings may promote more addictive behaviors.25

Because binge eating and food addiction are associated with challenges regulating emotions,26,27 food can be used as a way to self-medicate and temporarily feel better. (Foods with sweet tastes are especially effective at elevating mood and suppressing pain.28)

Food addiction is also associated with a history of trauma and abuse, and is found alongside a number of other mental health disorders like depression, attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), psychosis,29 and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).30

(Want to support clients with trauma while staying in your scope? Read: How trauma affects health and fitness—and prevents client progress)

Although many people think of addictive eating as a form of “self-sabotage,” here’s a more compassionate, useful way to think about it:

For the person struggling, food is simply a safe place, a comfort to turn to when life feels overwhelming.

Social factors: What’s around you?

In animal research, addictive eating behaviors only happen when they’re given highly-processed foods.5

This isn’t to say that processed foods cause addictive eating. It’s just that their presence, combined with other biological and psychological vulnerabilities, makes food addiction more likely.

And due to social factors, some people are exposed to highly-processed foods more often than others.

Imagine you live in a “food desert”—an area that has poor access to affordable, fresh, and minimally-processed food. If all you can get at your local grocery store is packaged snack foods, white bread, and maybe some canned fruit, your nutrition and appetite will be harder to manage.

Similarly, not having enough money to buy healthy foods on a regular basis can make an impact. Naturally, you might do like our ancestors and “stock up” when calories are available. Some research supports this: Higher rates of food insecurity are associated with disordered eating behaviors like binge eating.31

You can also pick up on social cues around food.

If you’ve grown up with friends and family that regularly overeat, or use food to soothe, comfort, or entertain, they might encourage you (explicitly or implicitly) to do the same.

Even when you want to change, swimming against the current can be hard.

The irony of diet culture

Despite some progress through movements like body positivity and “Health at Every Size,” modern culture still prizes thinness.

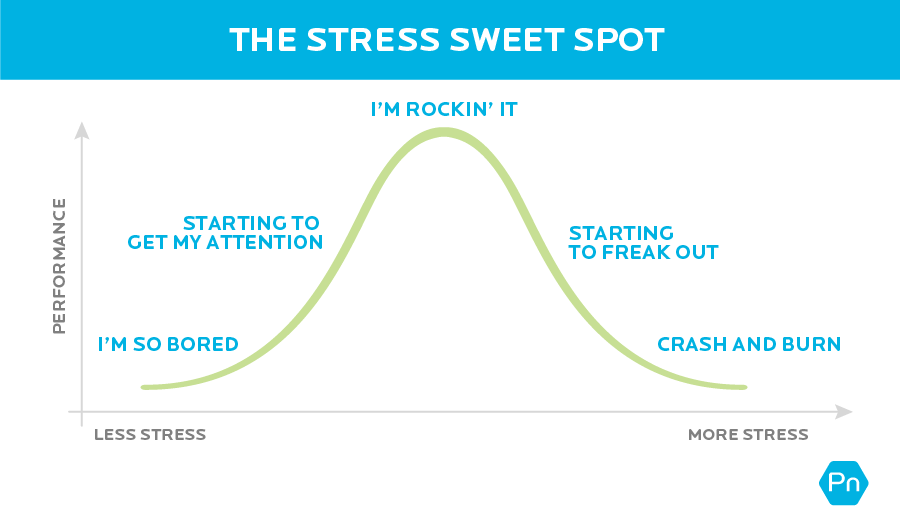

In order to achieve that thinness, many people diet incessantly.

Here’s how that backfires:

When you think you can’t have access to something (in this case, food you find delicious), you end up wanting more of it.

This is called the limited access paradigm, and it explains why very restrictive diets not only often fail, but may even make people more likely to overeat and binge eat.32

[Facepalm.]

That’s why recovery from compulsive overeating and food addiction often focuses on body awareness, mindful eating, and developing a positive relationship with food—not dieting.

Interested in checking your bias towards thinness as a coach? Read: Are you body-shaming clients? How well-meaning coaches can be guilty of “size-bias.”

Help with food addiction: 3 ways to support clients (or yourself)

Health and nutrition coaches can’t diagnose or treat a food addiction, or any kind of eating disorder. But you can start the conversation, and be an essential part of a client’s recovery team.

If you’re reading this article because you’re struggling, we’ll suggest some ways to support yourself too.

1. Create a safe, compassionate, and encouraging environment.

If a client comes to you with some deep stuff, don’t feel like you have to figure out their childhood or fix their biology.

Instead, focus on understanding their current situation, helping them feel safe, and developing a trusting relationship.

The best ways to do that? Practice empathy and active listening.

(Read more about empathy and listening skills: “I’m a coach, not a therapist!” 9 ways to help people while staying within your scope.)

Because people with food addiction and binge eating disorder may be more sensitive to reward,33,34,35 coaches can also help “reward” clients in more affirming ways.

Meaning: Give them lots of praise. Celebrate every “win” you see.

And if a client comes to you feeling shame over a certain behavior or feeling, reassure them that this isn’t evidence of their inadequacy. Missteps and imperfections are human. Feeling sensitive to them is just a sign that they want to do better for themselves.

If you’re struggling with food addiction:

You’ll benefit from self-compassion and non-judgement too. Try not to blame or criticize yourself for “causing” this or “being too weak” to pull yourself out of it.

Be your own buddy: People are much better at changing when they come from a place of love and support.

For more practical, self-compassionate ways to feel better, read: “How can I cope RIGHT NOW?” These self-care strategies might help you feel better.

2. Drop the nutrition lecture.

Yes, maybe you’re a health or nutrition coach.

But in this case, focusing too much on nutrition (especially calories and energy intake) can backfire.

Clients struggling with food addiction are usually already overly concerned with what and how much they’re eating—and they probably feel tremendous shame around that.

➤ Instead of nutritional value, focus on how foods make clients feel.

You can ask (with kindness and genuine curiosity): “When you eat [insert trigger food], how do you feel in your body? And what thoughts come up?”

Although sometimes uncomfortable, this exercise can help clients identify foods that do feel good in their bodies, and align with their values. Over time, this can build a more positive, practical relationship with food.

➤ Help clients develop awareness around their triggers.

Ask gently: “What was going on before you started to feel the urge to eat? Where were you, who were you with, and how were you feeling?”

When you’re aware of your patterns and habits, it’s easier to find opportunities to re-route them.

(Here’s a worksheet that helps clients identify and disrupt unproductive eating habits: Break the Chain worksheet)

➤ Collaborate to come up with eating-replacement activities.

Stress is a common trigger for overeating, so ask your client to make a list of activities that calm them down, and bring them joy.

Note that overeating isn’t “forbidden.” Clients always have the option to use this coping mechanism.

But they can also slowly develop alternative behaviors to eating—which they may learn to prefer over time.

If you’re struggling with food addiction:

Here are three small actions you can take to start helping yourself feel better:

Focus on how foods make you feel rather than their caloric value.Use the Break the Chain worksheet to develop awareness of your triggers.Create your own personal list of replacement activities.

3. Refer out.

If you suspect your client has food addiction, you may want to start with this worksheet: The Yale Food Addiction Scale. While you can’t diagnose your client (unless you’re also a qualified mental health or medical health professional), you can use this tool to begin a conversation.

Most importantly, empower your client to seek help outside of your coaching. Remind them that seeking professional help takes courage and wisdom, and that you’ll be with them along the ride.

For most people, a family doctor is a good place to start. Family doctors can perform a formal assessment, then refer to appropriate help, whether that’s a licensed therapist, a psychiatrist, or another health professional.

If your client wants help finding a therapist, find one that’s trained in cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), which has been shown to be effective in managing and treating addictions and disordered eating.

You might be the first (and only) person your client has confided in.

Take your role seriously, display acceptance and compassion, and help your client get the care they deserve.

If you’re struggling with food addiction:

You’re not supposed to do really hard things by yourself. It often takes a team of support, so reach out.

Talk to a trusted loved one for moral support, and consult your family doctor or a licensed psychotherapist to get professional help.

Asking for help doesn’t make you weak. It means you have your own back.

jQuery(document).ready(function(){

jQuery(“#references_link”).click(function(){

jQuery(“#references_holder”).show();

jQuery(“#references_link”).parent().hide();>

References

Click here to view the information sources referenced in this article.

1. Imperatori, Claudio, Mariantonietta Fabbricatore, Viviana Vumbaca, Marco Innamorati, Anna Contardi, and Benedetto Farina. 2016. “Food Addiction: Definition, Measurement and Prevalence in Healthy Subjects and in Patients with Eating Disorders.” Rivista Di Psichiatria 51 (2): 60–65.

2. Schulte, Erica M., Julia K. Smeal, Jessi Lewis, and Ashley N. Gearhardt. 2018. “Development of the Highly Processed Food Withdrawal Scale.” Appetite 131 (December): 148–54.

3. Berkman, Nancy D., Kimberly A. Brownley, Christine M. Peat, Kathleen N. Lohr, Katherine E. Cullen, Laura C. Morgan, Carla M. Bann, Ina F. Wallace, and Cynthia M. Bulik. 2015. Table 1, DSM-IV and DSM-5 Diagnostic Criteria for Binge-Eating Disorder. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US).

4. Bonder, Revi, Caroline Davis, Jennifer L. Kuk, and Natalie J. Loxton. 2018. “Compulsive ‘Grazing’ and Addictive Tendencies towards Food.” European Eating Disorders Review: The Journal of the Eating Disorders Association 26 (6): 569–73.

5. Davis, Caroline. 2013. “From Passive Overeating to ‘Food Addiction’: A Spectrum of Compulsion and Severity.” ISRN Obesity 2013 (May): 435027.

6. Brown, Elizabeth A. 2012. “Genetic Explorations of Recent Human Metabolic Adaptations: Hypotheses and Evidence.” Biological Reviews of the Cambridge Philosophical Society 87 (4): 838–55.

7. Neel, James V. 2009. “The ‘thrifty Genotype’ in 19981.” Nutrition Reviews 57 (5): 2–9.

8. Wiss, David A., Nicole Avena, and Pedro Rada. 2018. “Sugar Addiction: From Evolution to Revolution.” Frontiers in Psychiatry / Frontiers Research Foundation 9 (November): 545.

9. Davis, Caroline. 2014. “Evolutionary and Neuropsychological Perspectives on Addictive Behaviors and Addictive Substances: Relevance to the ‘Food Addiction’ Construct.” Substance Abuse and Rehabilitation 5 (December): 129–37.

10. Lutter, Michael, and Eric J. Nestler. 2009. “Homeostatic and Hedonic Signals Interact in the Regulation of Food Intake.” The Journal of Nutrition 139 (3): 629–32.

11. Small, Dana M., Marilyn Jones-Gotman, and Alain Dagher. 2003. “Feeding-Induced Dopamine Release in Dorsal Striatum Correlates with Meal Pleasantness Ratings in Healthy Human Volunteers.” NeuroImage 19 (4): 1709–15.

12. Kelley, Ann E., Brian A. Baldo, and Wayne E. Pratt. 2005. “A Proposed Hypothalamic-Thalamic-Striatal Axis for the Integration of Energy Balance, Arousal, and Food Reward.” The Journal of Comparative Neurology 493 (1): 72–85.

13. Monteleone, Palmiero, Fabiana Piscitelli, Pasquale Scognamiglio, Alessio Maria Monteleone, Benedetta Canestrelli, Vincenzo Di Marzo, and Mario Maj. 2012. “Hedonic Eating Is Associated with Increased Peripheral Levels of Ghrelin and the Endocannabinoid 2-Arachidonoyl-Glycerol in Healthy Humans: A Pilot Study.” The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism 97 (6): E917–24.

14. Garavan, Hugh, and Karen Weierstall. 2012. “The Neurobiology of Reward and Cognitive Control Systems and Their Role in Incentivizing Health Behavior.” Preventive Medicine 55 Suppl (November): S17–23.

15. Volkow, Nora D., Gene-Jack Wang, Dardo Tomasi, and Ruben D. Baler. 2013. “The Addictive Dimensionality of Obesity.” Biological Psychiatry 73 (9): 811–18.

16. Gluck, Marci E. 2006. “Stress Response and Binge Eating Disorder.” Appetite 46 (1): 26–30.

17. Davis, C. 2009. “Psychobiological Traits in the Risk Profile for Overeating and Weight Gain.” International Journal of Obesity 33 Suppl 2 (June): S49–53.

18. Moreno-López, Laura, Carles Soriano-Mas, Elena Delgado-Rico, Jacqueline S. Rio-Valle, and Antonio Verdejo-García. 2012. “Brain Structural Correlates of Reward Sensitivity and Impulsivity in Adolescents with Normal and Excess Weight.” PloS One 7 (11): e49185.

19. Wang, Gene-Jack, Allan Geliebter, Nora D. Volkow, Frank W. Telang, Jean Logan, Millard C. Jayne, Kochavi Galanti, et al. 2011. “Enhanced Striatal Dopamine Release during Food Stimulation in Binge Eating Disorder.” Obesity 19 (8): 1601–8.

20. Wang, Gene-Jack, Nora D. Volkow, Panayotis K. Thanos, and Joanna S. Fowler. 2009. “Imaging of Brain Dopamine Pathways: Implications for Understanding Obesity.” Journal of Addiction Medicine 3 (1): 8–18.

21. Bello, Nicholas T., and Andras Hajnal. 2010. “Dopamine and Binge Eating Behaviors.” Pharmacology, Biochemistry, and Behavior 97 (1): 25–33.

22. Davis, Caroline, Robert D. Levitan, Zeynep Yilmaz, Allan S. Kaplan, Jacqueline C. Carter, and James L. Kennedy. 2012. “Binge Eating Disorder and the Dopamine D2 Receptor: Genotypes and Sub-Phenotypes.” Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology & Biological Psychiatry 38 (2): 328–35.

23. Davis, Caroline A., Robert D. Levitan, Caroline Reid, Jacqueline C. Carter, Allan S. Kaplan, Karen A. Patte, Nicole King, Claire Curtis, and James L. Kennedy. 2009. “Dopamine for ‘Wanting’ and Opioids for ‘Liking’: A Comparison of Obese Adults with and without Binge Eating.” Obesity 17 (6): 1220–25.

24. Frayn, Mallory, Christopher R. Sears, and Kristin M. von Ranson. 2016. “A Sad Mood Increases Attention to Unhealthy Food Images in Women with Food Addiction.” Appetite 100 (May): 55–63.

25. Craven, Michael P., and Erin M. Fekete. 2019. “Weight-Related Shame and Guilt, Intuitive Eating, and Binge Eating in Female College Students.” Eating Behaviors 33 (April): 44–48.

26. Tatsi, Eirini, Atiya Kamal, Alistair Turvill, and Regina Holler. 2019. “Emotion Dysregulation and Loneliness as Predictors of Food Addiction.” Journal of Health and Social Sciences 4 (1): 43–58.

27. Cassin, Stephanie E., and Kristin M. von Ranson. 2005. “Personality and Eating Disorders: A Decade in Review.” Clinical Psychology Review 25 (7): 895–916.

28. Gibson, E. Leigh. 2012. “The Psychobiology of Comfort Eating: Implications for Neuropharmacological Interventions.” Behavioural Pharmacology 23 (5-6): 442–60.

29. Stunkard, Albert J. 2011. “Eating Disorders and Obesity.” The Psychiatric Clinics of North America 34 (4): 765–71.

30. Hardy, Raven, Negar Fani, Tanja Jovanovic, and Vasiliki Michopoulos. 2018. “Food Addiction and Substance Addiction in Women: Common Clinical Characteristics.” Appetite 120 (January): 367–73.

31. Hazzard, Vivienne M., Katie A. Loth, Laura Hooper, and Carolyn Black Becker. 2020. “Food Insecurity and Eating Disorders: A Review of Emerging Evidence.” Current Psychiatry Reports 22 (12): 74.

32. Babbs, R. K., F. H. E. Wojnicki, and R. L. W. Corwin. 2012. “Assessing Binge Eating. An Analysis of Data Previously Collected in Bingeing Rats.” Appetite 59 (2): 478–82.

33. Loxton, Natalie J., and Renée J. Tipman. 2017. “Reward Sensitivity and Food Addiction in Women.” Appetite 115 (August): 28–35.

34. Loxton, Natalie J. 2018. “The Role of Reward Sensitivity and Impulsivity in Overeating and Food Addiction.” Current Addiction Reports 5 (2): 212–22.

35. Eneva, Kalina T., Susan Murray, Jared O’Garro-Moore, Angelina Yiu, Lauren B. Alloy, Nicole M. Avena, and Eunice Y. Chen. 2017. “Reward and Punishment Sensitivity and Disordered Eating Behaviors in Men and Women.” Journal of Eating Disorders 5 (February): 6.

Precision Nutrition Level 1 Certification. The next group kicks off shortly.

–>

If you’re a coach, or you want to be…

Learning how to coach clients, patients, friends, or family members through healthy eating and lifestyle changes—in a way that’s personalized for their unique body, preferences, and circumstances—is both an art and a science.

If you’d like to learn more about both, consider the Precision Nutrition Level 1 Certification.

Precision Nutrition Level 1 Certification.

–>

The post Food addiction: Why it happens, and 3 ways to help (or get help). appeared first on Precision Nutrition.