Imagine life with nothing to challenge you, change you, or encourage you to grow.

Sounds like a total snooze, right?

Well, that’s a life with no stress.

In reality, we want a “Goldilocks amount” of stress: not too much, but also not too little.

So why does so much of the advice around stress management tell you to simply “reduce stress”?

Is that really the right approach, all the time?

Stress itself isn’t a bad thing.

A stressor is simply something that disrupts homeostasis (the status quo).

By itself, a stressor is neutral.

Instead, it’s how you react to a stressor—your physiological and psychological stress response—that determines its positive or negative impact.

How you perceive, experience, and cope with stress not only influences how you behave, but also how stress affects you. In other words, whether it breaks you down—or builds you up.

For instance: Do you like the sound of grown men screaming and growling?

If not, you probably don’t like Norwegian death metal music, and would find it horribly stressful to hear.

If yes, that might be just the thing to help you relax after a tough day.

Same stimulus: different perception, different response.

Luckily, no matter your starting point, you can develop the skills to embrace, manage, and even grow from stress.

The result: You can feel more capable and live a richer, fuller life.

We’ll show you how—with three strategies that’ll help you build resilience and make stress work for you.

(But don’t worry: Norwegian death metal is completely optional.)

When you embrace stress, it can benefit all areas of your life.

In the right amounts—and with effective responses to it—stress can keep you interested, energized, growing, productive, and connected. Stress can give all areas of life substance and meaning.

Check it out:

Dimension of healthHow stress helps usPhysical healthStressors can energize you, sharpen your senses, and increase your ability to withstand discomfort.

Intermittent stress—coupled with recovery—helps your body become stronger and more capable.Mental and cognitive healthManaged effectively, stress helps you focus your attention, plan for future challenges, and enhance memory and learning. Stressors might even feel like fun puzzles to solve.Emotional healthStress can help you develop heightened awareness, stronger relationships, and a greater appreciation for the ups and downs of life.Social healthSome conflict is actually crucial for healthy, secure relationships—it’s a pathway to better understand others. By working through things together, we grow together.Existential healthNothing makes you feel alive like facing a crisis and emerging on the other end with a new sense of self, purpose, and priorities.

It’s often when your values and purpose are threatened that you’re most energized to commit to them.Environmental healthHeat! Cold! Rough terrain! Variations in your environment help you get stronger and more adaptable.

(E.g. Exercising in hot, humid temperatures is hard and initially slows you down, but over time, increases your oxygen capacity and your ability to manage heat.)

Pretty cool, right?

Like a piece of coal, a little bit of pressure can help the diamond emerge.

How to use stress to build you up, instead of break you down

Of course, stress won’t always be present in the “right” amount.

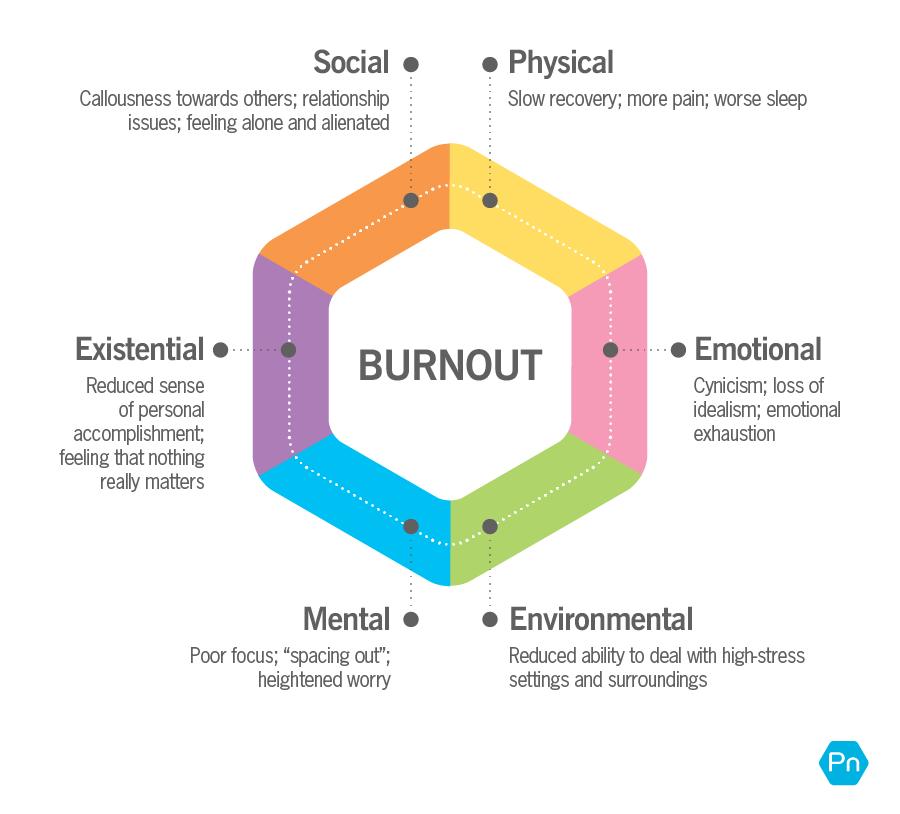

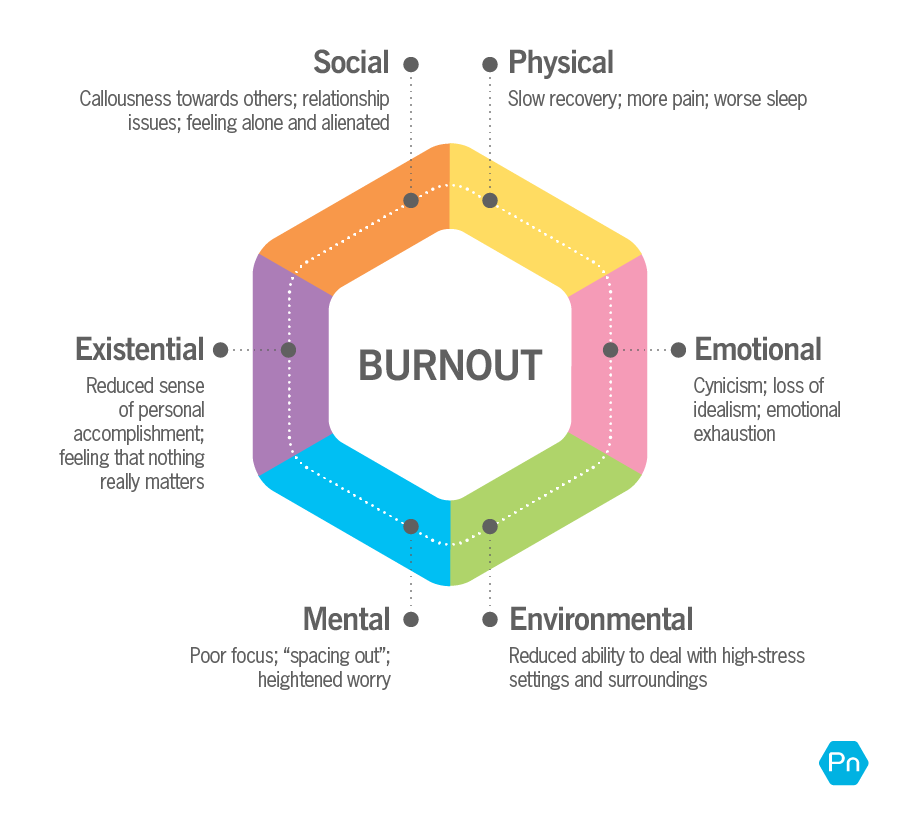

And some types of stress shouldn’t be “leaned into.” Chronic stressors like abuse, unsafe communities, a global pandemic, racism, homophobia, and so on can harm people’s health.

If stress is unrelenting, demoralizing, and feels completely out of your control, take steps to reduce it and protect yourself and your sanity, if you can.

Concerned that you might be burned out? Take our burnout quizFeeling overwhelmed by stress and anxiety? Read: “How can I cope RIGHT NOW?” These self-care strategies might help you feel better.Discover how trauma affects health and fitnessLearn how to prioritize self-care… without the bubble bath.

But, if and when you do have the opportunity, you can actually increase your capacity for stress by changing how you perceive and process it

When you build your “stress coping muscle,” what you used to think of as overwhelming becomes an exciting challenge.

(Think: things like demanding work assignments, physical training, and change in general.)

Here are three strategies to help you use stress to your advantage.

Strategy 1: Change your stress mindset.

Your mindset is the mental lens through which you look at the world.

It’s like a framework for organizing your beliefs, assumptions, and perspective.

Your mindset makes meaning out of your experiences. In turn, it shapes your actions and responses during those experiences.

In a sense, your mindset is a self-fulling prophecy.

When you believe…

Stress is an assetStress is harmfulYou’ll be more likely to:

Feel, think, act, and respond in ways that improve your performance and encourage flexibility and resourcefulnessEngage in active coping behaviors, and actually resolve your problemsNotice evidence of your resilience, which reinforces your beliefLong-term, build deep health and fitness, making you even more capable and resilient in futureMeet new challenges, and believe you’re able to meet those challengesYou’ll be more likely to:

Feel, think, act, and respond in ways that make you less resilient and more at risk of negative consequences of stressFocus on how bad you feel, finding plenty of evidence of your “failures” and distressFear the future and what could happen, because you don’t trust your own ability to deal with itSteer clear of situations that could lead to growth

Cope with stressors unproductively, avoiding or ignoring your problems (ironically making stressors bigger and longer-lasting)

Try it: Do a stress audit.

Shifting your mindset can take time and practice. And, you may have to purposely face challenging events to learn that you can recover from them.

However, you can begin to change your stress mindset with this exercise:

Make three columns.

In the first column, list all the challenging or stressful events you’ve experienced in the last year or two.

Some of those were probably really hard to go through. While you were “in it,” it might’ve been hard to see your way out.

But here you are.

Now, in the second column, note what you learned from these events. What skills were you forced to develop, and what wisdom did you gain from them?

Last, in the third column, list the resources that helped you manage and overcome these challenges. What knowledge, emotional resilience, or social support did you draw on?

Consider what you have in front of you.

Sure, there are some experiences that we would never wish to repeat, and not all stressful events make us stronger. (Again, it’s important to distinguish between healthy stressors and burnout or traumas.)

But you might notice that many challenges—even the unwelcome ones—serve you in the long term, making you more compassionate, gritty, or wise.

When you consider future challenges, draw on this list.

What can you borrow from previous experiences that might help you?Or, are there any areas that you might want to develop to help you feel better equipped?

When you believe your ability to cope matches or exceeds the demand of a situation, you’re more likely to look at that situation as a challenge rather than a threat.

(Not only does this help you feel better, but physiologically, you’re less likely to experience the negative health effects of stress, like high cortisol.1)

Feeling prepared and well-resourced helps you approach growth opportunities—and make life’s inevitable flash storms feel a lot less scary.

Strategy 2: Develop productive coping strategies.

Ironically, avoiding and ignoring stress, or trying to reduce it across the board, can create a vicious cycle:

The more you try to run away from stress, particularly using unhelpful coping strategies, the worse it gets.

However, there’s also a virtuous (positive) cycle that can go in the exact opposite direction:

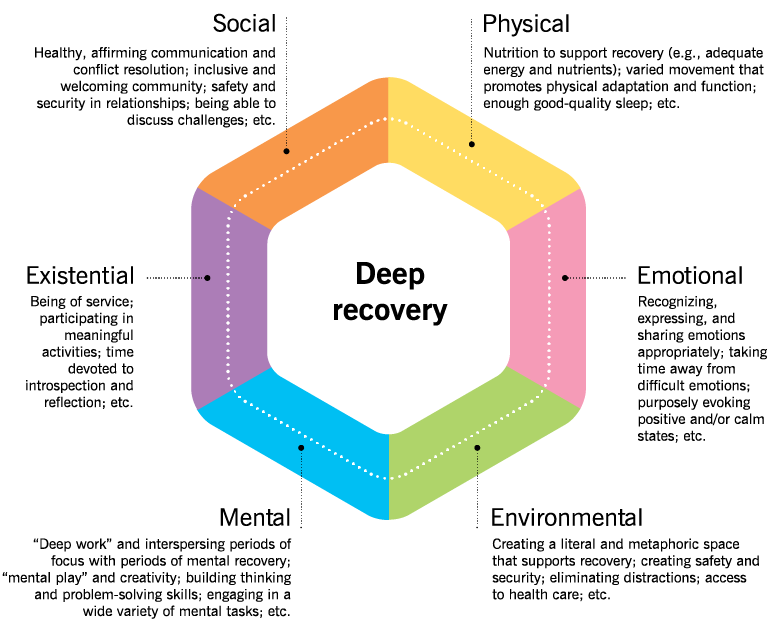

You embrace stress, use productive coping mechanisms to help yourself process and recover, and actually improve your health—not to mention your resilience to future stressors.

The below table describes the differences between these two coping styles:

Productive copingUnproductive copingCan cause short-term discomfort but ultimately leads to better long-term outcomeTries to alleviate short-term discomfort but ends up creating long-term problemsApproach-focused: Deals directly with the problem or situationAvoidance-focused: Avoids dealing with the problem or situationFaces and accepts reality as it isDenial and wishful thinking (“If only this hadn’t happened…”)Assertive, activeDefensive, passive, helplessOptimism, belief in one’s ability to manageHopelessness, despair, resignationHealthy de-stressing (e.g., exercise, meditation, social support)Unhealthy distractions and numbing-out (alcohol, drugs, compulsive shopping)Thinking practically about how to address the situation (e.g., coming up with possible solutions)Rumination (constantly thinking about the situation and how bad or upsetting it is)

Try it: Practice a productive coping style with 5-minute actions.

Tiny, strategic, 5-minute steps can help you start approaching and proactively dealing with stressors—especially when they feel overwhelming and make you want to run away,

We call it the 5-minute action.

(Although there’s nothing special about 5 minutes. It could be 10 seconds, or 1 minute, or 10 minutes.)

The point is:

It’s something that’s very, very small.It’s an action—something you do.It feels easy and simple.It moves you in the direction you want to go.

So, consider the thing you’re stressed about.

Then pick ONE small action you can take TODAY to help deal with it.

(To identify an action that will actually help you achieve your larger goal, check out The 4-Circle Exercise.)

Here’s an example:

If you’re stressed about your eating habits, your 5-minute action might be to place an online grocery order, so you have access to healthy foods for the next week. (Or, find a healthy meal delivery service if you don’t have time to cook, and you can afford to delegate that task.)

Each time you choose a productive coping strategy instead of an unproductive one, it’s like a biceps curl for your resilience muscle. Eventually, your instinct to choose productive coping gets stronger, and stress actually becomes a catalyst for growth.

Strategy 3: Learn how to turn on productive stress… and how to turn it off.

Being a little amped up is great when you’re trying to line up a free throw to score the winning point, when you’re writing an exam, or when you’re having an important, meaningful discussion with your partner.

However, you also want to be able to turn off your stress response when you need to rest.

You want “stress flexibility.”

In practical terms, that means:

A strong sympathetic nervous system response to mobilize action when it’s “go time” (such as a job interview, audition, or athletic competition).A strong parasympathetic nervous system response to calm you down when it’s “chill time” (such as bedtime).A relatively calm but attentive baseline in between.

More resilient people can rapidly turn their stress response on and off as needed, and match its intensity to the challenge at hand.

Try it: Practice coping flexibility.

To be able to turn “on” and “off” when you need to, you’ll want to have a full toolbox of coping strategies to help you deal with, process, and recover from different types of stressful situations.2

This is called “coping flexibility.”

There’s no one best (productive) coping method that works for everything and everyone, but these are some of our favorites:

Make time and plan ahead: Organize your schedule and routine to focus on valued activities (such as sleep), and anticipate reasonable obstacles. (For help, check out: Planning & Time Use WorksheetDo a mind/body scan: Take five to ten minutes mentally scan your body from head to toe, noticing physical sensations, emotions, and thoughts.Have a crucial conversation: Have important yet difficult discussions; confront and discuss an “elephant in the room” (that cringe-y issue you’re avoiding) with someone you care about.Practice self-compassion: Offer care, kindness, and grace to yourself during difficult times. Ask yourself: ‘How can I be most kind to myself during this experience?’Identify bright spots: Focus almost exclusively on what is going well; ignore problems and setbacks unless they’re actively causing damage. Ask yourself: ‘What is going well, even just a little bit? What strengths, resources, and opportunities do I have right now?’Just breathe: Use breathing techniques to energize or calm your body. (Try “box breathing”: Inhale for 4 to 5 seconds, hold that breath for 4 to 5 seconds, slowly breathe out for another 4 to 5 seconds, and then hold your breath for 4 to 5 seconds more. Repeat as many times as you like.)Seek support: When possible, avoid going into the proverbial woods alone. Whether friends and family; your dog who always listens without interrupting; or a qualified counselor or therapist—find support, allies, and buddies to walk the path with you. Others help “co-regulate” us by providing a comforting presence.

Stress management is a choose-your-own-adventure.

Stress management can be about lowering your load of stressors.

Often, that’s a great option.

If you honestly assess your life and your ability to affect it, you’ll usually find plenty of areas that are within your control.

In these cases, you can lower unproductive stressors, like avoidable conflicts with friends and family, spending too much time doomscrolling social media thinking about how much the world sucks, and so on.

However:

Stress management can also be about rising to the challenge in areas you care about, or want to grow in.

For instance, maybe…

You watch a few hours less TV a week to take a language class that stretches your brain.You enlist coaching to take your sport to the next level, or sign up for an event that’s just a little harder or scarier than what you can do now.You sign up for Toastmasters, improv, or a standup comedy class to finally confront that fear of public speaking.You challenge yourself to be a better parent or partner by working on your own communication skills.You address injustice in the world by finding allies and working for change.

Ultimately, stress management is about choosing.

Where possible, you can choose what stressors you expose yourself to. Seek challenges in the areas you want to grow, and lower the threats in the areas that are harming you.Where you can’t change the stressors, you can try to choose your response. Learn calming and self-regulating skills, and productive ways to cope. If you find you consistently can’t change your response to stressors, seek help.

(Expert tip: At some point, choose support rather than going it alone. A trusted friend or family member, coach, and/or qualified mental health professional can help you build a strong stress-resilience team.)

When you have choices, you’re less likely to feel stuck.

So when that big life-avalanche comes barreling your way, you don’t feel doomed.

Instead, you might think, “I’m ready. I can ride this beast.” (Maybe even while turning the Norwegian death metal up to 11.)

jQuery(document).ready(function(){

jQuery(“#references_link”).click(function(){

jQuery(“#references_holder”).show();

jQuery(“#references_link”).parent().hide();>

References

Click here to view the information sources referenced in this article.

1. Uphill, Mark A., Claire J. L. Rossato, Jon Swain, and Jamie O’Driscoll. 2019. “Challenge and Threat: A Critical Review of the Literature and an Alternative Conceptualization.” Frontiers in Psychology 10 (July): 1255.

2. Cheng, Cecilia, Hi-Po Bobo Lau, and Man-Pui Sally Chan. 2014. “Coping Flexibility and Psychological Adjustment to Stressful Life Changes: A Meta-Analytic Review.” Psychological Bulletin 140 (6): 1582–1607.

If you’re a health and fitness coach…

Learning how to help clients manage stress, build resilience, and optimize sleep and recovery can be deeply transformative—for both of you.

It helps clients get “unstuck” and makes everything else easier—whether they want to eat better, move more, lose weight, or reclaim their health.

And for coaches: It gives you a rarified skill that will set you apart as an elite change maker.

The brand-new PN Level 1 Sleep, Stress Management, and Recovery Coaching Certification will show you how.

Want to know more?

The post What Norwegian death metal can teach you about stress management. appeared first on Precision Nutrition.

Did you miss our previous article…

https://trailsmart.org/?p=124